The most important, most prescient thing I have heard in my life about the true doom of AI being set upon mankind didn’t come from a skinny white silicon valley dude in a Ted Talk or a futurist rationalist investment banking bitcoin bro, nor even the 2012 classic Whispering Ear Ring story by Scott Alexander. It came from an old black lady teaching seventh grade science class in 1988 opining on the nature of public education.

The Wisdom of Mrs. Sadler

Pronounced “Satler,” no “D,” Mrs. Sadler was my seventh grade science teacher at Marietta Junior High, an urban profile public school on the outskirts of Atlanta Georgia walking distance from the Baptisttown Housing Projects.

She was the roundest, loudest, blackest, most matronly teacher I have ever had. Imagine Aunt Jemima teaching chemistry, before the wokes destroyed the longest running logo and trademark in the history of US advertising under protest from the Aunt Jemima models actual descendants. Mrs. Sadler was the oldest, most respected, and most beloved teacher at Marietta Junior High, the PTA liaison, and a character beyond reproach.

I had a friend named Geoff Clark. The first day Mrs. Sadler called roll, she called “Gee Off Clark.” We laughed. “That’s Jeff,” he phonetically corrected her. She got it wrong the second day, and he phonetically corrected her again. She made a note in the roll, got his name right the third and fourth days, and on Friday when she passed out our first quiz she called “Gee Off Clark.” When he attempted to correct her again she quipped, “If you named Jeff, why you keep puttin Gee Off on your paper?” This may have been the funniest thing a room full of seventh grade boys had ever heard. We had no idea if our leg was being pulled. That was the nature of the dialogue in this class.

On a later day, I cannot recall the exact context, the class discussion revolved around the fundamental nature and mission of public schooling. Someone mentioned learning. The base wisdom that flowed from Mrs. Sadler burned into my brain so deeply I can directly quote it to this day with no error.

Sadler: “Why you think you here?”

Students: “To Learn?”

Sadler: “Learn! You ain't here to learn. You here to exercise your brain.”

Students: …

Sadler: “You know they teach a monkey sign language right?”

Students: …

Sadler: “A monkey! They teach that monkey sign language. What you gonna do for a job when you grow up? Front line at Mack Donalds? A monkey could do that. What’s the difference between you and a monkey?”

I feel the need to pause this story to mention that Marietta City Schools, sporting a healthy and diverse blend of racial and ethnic backgrounds while enjoying deep and robust funding from the elite gentry of “Ole Mayretta,” was well ahead of the curve on things like racial consciousness, and the blend of seventh graders in Merit Science were not about to say a single thing about monkeys in this context. This moment may have been the most silent moment this rowdy bunch of early adolescent miscreants experienced all year.

Sadler: “Difference between you and a monkey is you exercise your brain. That monkey’s just up in a tree eating bananas and you’re in school, exercising your brain. That’s why you’re here. You ain’t here to learn.”

I cannot in this moment tell you a single thing I learned in seventh grade science class. I don’t recall the curricula, the tests, the homework, or any single fact. I recall the above two instances, and I recall exercising my brain. And this bit of base wisdom is of more import to the current state of societal adoption of generative AI tools than anything you will see on a Ted Talk.

Beyond Seventh Grade Science

Budzyn et al on August 12th published a multicenter observational study in The Lancet of the ACCEPT trial, which stands for Artificial Intelligence in Colonoscopy for Cancer Prevention. Nineteen doctors participated in the study, which used AI tools to evaluate colonoscopies. They found that the AI tools did a good job of identifying cancer, but the doctors who used them got measurably worse at it after the trial concluded. These were not green recruits, each doctor in the study had several thousand colonoscopies under their belt.

Kosmyna et al at MIT found a similar effect this year when evaluating essay writing skill. Using the AI led to a progressive decline in critical thinking and memory.

Rinta-Kahila et al identified a similar pattern in 2023 in the Journal of the Association for Information Systems, when they studied an accounting firm which pivoted over to AI based workflow automation.

Boston Consulting Group identified gains in business consulting output from less skilled workers but indicated the experts using the tools “deskilled.”

Handwaving Freakoutery used Perplexity.ai to do all the research for this piece without once digging through library microfiche.

And so forth.

Witty Third Section Title Generated By AI

The emerging science of AI driven “deskilling” is not very likely to catch up to mankind’s adoption of these tools, and the results are easily predictable. More technical jobs will be doable by less technical people and this will impact the overall technology sector and the people who live and work in it. The net effect on the species will be that we get dumber on-net, lacking professional brain exercise.

At the risk of assigning prophet status to Mrs. Sadler, it seems likely to me that the 22nd century will have a few more monkeys eating bananas and a lot fewer folks who know how to grow them. I’ve seen a quote circulating recently that “AI is the modern day equivalent of asbestos - we’re putting it in everything, and in twenty years it’ll cost a fortune to take it out again.” My fear, unfortunately, is that in twenty years we’ll have lost the skill to remove it.

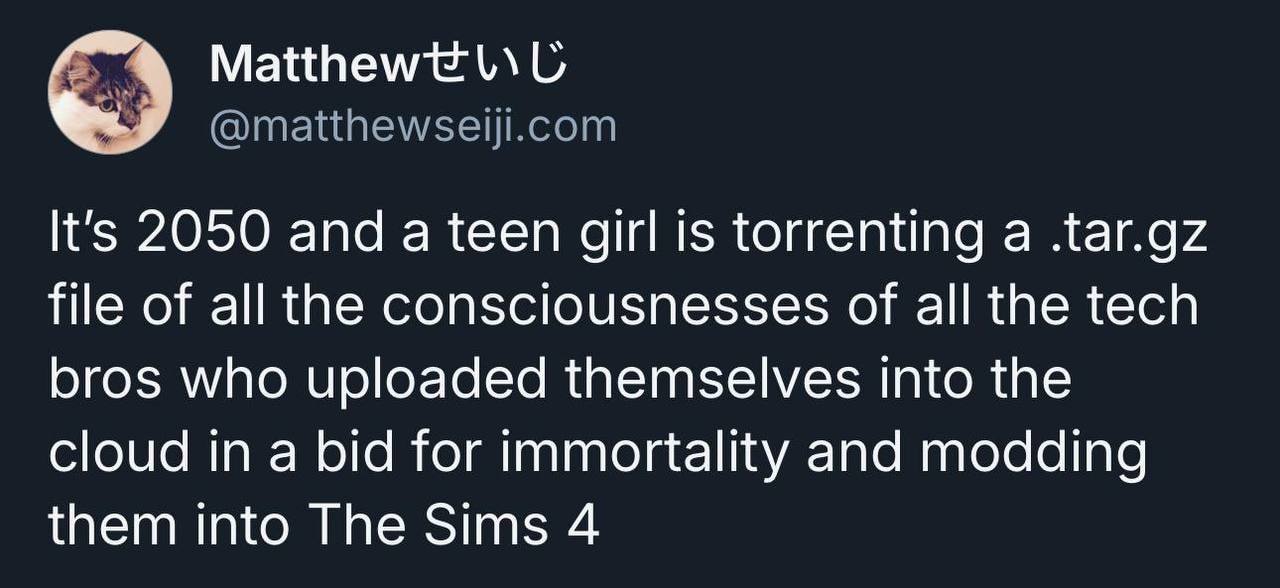

I think we’ll probably still keep a strong meme game though.

As I replied to Tyler Cowen's Free Press article promoting the use of AI in writing college papers:

I can use a forklift to lift my barbells for me, and I can put a lot more weight on than I can lift myself. Will that make me stronger?

The purpose of writing papers is not to produce papers. It's to learn the content.

Note that you make a distinction between unimportant skills (what you learned in your 7th grade class) and learning how to think, and then list as examples of the problem with AI specific skills that are becoming atrophied (medical diagnostics, essay writing, becoming "deskilled"). The real question is whether or not people are becoming atrophied in their ability to do critical thinking. Perhaps they are. Perhaps AI is causing an intellectual laziness. Or perhaps these abilities are moving elsewhere (how to write good prompts, how to better delegate tasks, how to use AI effectively). It's probably a mix. Social media has certainly had mixed results (and as someone raised before it, I preferred life without it, but that could be generational).

I don't discount the risk of AI - in fact, it terrifies me as much as it amazes me - but I think it's informative to follow people that are finding ways to use it to improve rather than replace thinking. For anyone that's interested, I recommend reading the Substack of Mike Caulfield - https://mikecaulfield.substack.com/ - who's been playing with LLMs to find ways to use them to teach argumentation (e.g. Toulmin analysis).