Allow me to take you on a ten minute ride about harmonic oscillating mathematical systems, bulldozers, civil engineering pranks, and a dude named Jack, ending in a prediction about a market sector that makes up one twentieth of the entire US economy. But first, my credentials.

My C. V.

My grandfather was in construction, my father was in construction, and I drove my first bulldozer (a CAT D3) when I was seven years old. It looked something like this.

I started in civil engineering at age sixteen, I have a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering and construction management from a top five nationwide program, a master’s degree in environmental fluid mechanics from the same program, and I’ve been in engineering for land development ever since. My wife was a construction project manager. I’m a licensed Professional Engineer (PE) in three states, and I have my fingers in dozens of large land development projects per year. I lived through the 1998 land development crash, the 2008 land development crash, and my family tells stories of every crash going back to World War Two. When I tell you the land development sector is about to crash, you should heed my words over any financial pundit, real estate agent, or media figure who claims to understand economics. The land development sector is about to crash. To understand why, let’s dial some some mathematical concepts down to their basics for reader comprehensibility.

Oscillating Systems

All mathematical systems which self-correct based on trailing indicators oscillate.

A flag flaps in the breeze because it experiences a constant state of overcorrection. The wind blows it right, it ends up in the path of the wind to the right which blows it left, repeat. If the flag somehow knew in advance that it was going too far to the right it could start bending left before reaching all the way right, and it could straighten out. But it doesn’t correct based on the future. A flag is a dumb thing that doesn’t know its future. Its current position is a trailing indicator of its future position, and it self-corrects based on the trailing indicator.

A clock pendulum works the same way – its angular acceleration is based on its current location, which is a trailing indicator of its future location, so it overcorrects. Springs work this way, and most of the easiest physics around “simple harmonic motion” were developed for springs because they’re easy to mess with in a lab.

But this same behavior extends all the way out to the most complicated dynamic systems in physics, which are fluid flow fields.

Going philosophical for a moment, everything in nature is an oscillation of some kind. Quantum fields are oscillations. String theory proposes the smallest elemental particle is an oscillating string. Life may never have developed on Earth were it not for the tides, which oscillated to churn the primordial ooze. All plant life is seasonal.

Economic systems are mathematical systems, and they self-correct based on trailing indicators, just like the above systems, therefore economic systems oscillate. And the period of oscillations in the construction sector is, on average, about ten years. We’re overdue. Here’s how that system works.

Case Study: Serenity Farms

Let’s say you live, as so many Americans do, in a house on a road in a subdivision with a big sign out front and a Homeowner’s Association that gives you a ration of shit if you paint your mailbox the wrong color. This subdivision was built by a land developer, who is basically some dude with connections to money, who wants to turn that money into more money by buying a cow field and turning it into the place you currently live. Herein, we tell the story of Serenity Farms, a generically named, wholly concocted fictional subdivision, built by Serenity Farms LLC, a legal entity brewed up by some jack leg in a pickup truck.

(disclaimer, there are probably a dozen actual developments called “Serenity Farms” in the USA and any similarities to them and the following description is purely coincidental, or perhaps systemic)

Mr. Jack Leg identifies that Townsville has a demand for 500 single family homes over the next decade. Mr. Leg finds a 60-acre family farm in disrepair, and hires a landscape architect out of pocket to draw a “land plan,” a pretty picture with fat markers and crayons of what that 60 acre farm would look like as a 50 lot residential subdivision. He carries that pretty picture to a bank (or to his golfing buddies) with a business plan for Serenity Farms LLC, an entity whose purpose is to buy this farm from the farmer, build the roads and utility infrastructure, subdivide the land, and sell the lots off to individual home builders. The land will cost him a million dollars, the infrastructure improvements are going to cost him another million, and he figures he can sell these lots to home builders for $60,000 each. This transaction will net him, and the bank, and his golfing buddies, a million in profit on the venture before he shuts the LLC down so he can’t be sued. In truth the margins on a project like this are often much thinner, but let’s continue with easy, round numbers.

The land plan takes two months to complete. The business plan takes two months. The negotiations with investors take another four months, and the negotiations to buy the family farm from the eight bickering grandkids who now own it in an agricultural trust take another four, so he’s a year into this business venture before it hits the zoning boards.

Now he hires a civil engineer, which leads the four-month rezoning effort with the local municipality, involving angry nearby residents, politicians, and opposing developers. Then the civil engineer must turn the fat lined pretty picture into something real, laying in the roads per code, designing the grades, the erosion control, the storm drainage, the detention pond, and the sanitary sewer utilities. The civil negotiates with the utility company to dump more sewage into their system, bickers with the local municipality about the storm water management regulations, must get approval from the fire department for fire lanes, and must also revise everything repeatedly because Mr. Leg keeps changing what he wants because his golfing buddies keep changing their minds about what they want. Mr. Leg is so unresponsive to his civil engineer that he won’t give the names he wants for his roads, which is how you occasionally get roads named like this:

Every time the engineer submits plans to the municipality for approval they give him “comments,” which require him to change the design. He does this three times, no matter how good or bad the initial design is, because without three rounds of comments the government thinks they’re not doing their job properly, and in the end the process of zoning and permit approval takes a year.

We’re two years in so far. Keep an eye on that.

Now the developer breaks ground. Earth is moved. Erosion controlled. Infrastructure installed. Curbs poured, roads paved, land surveyed, and the land is subdivided into smaller bits of land for sale to the next entity down the line. This takes another year, and Mr. Leg sells lots off to home builders. The process of sale of the lots takes yet another year, and after four years Jack Leg dissolves the LLC and hands the profits out to his golfing buddies, who all buy their next boat. But the houses aren’t built yet, and in the interim the demand of “500 single family homes” in the town has now grown to 1000.

Building the subdivision out takes another two years, meaning there’s a six-year lag between the identification of the demand and the meeting of that demand. This is what economists would call a very inelastic market. But Jack Leg wasn’t the only developer to identify this demand, his friends Jack Hole and Jack Sprat did so as well, and each put another 100 houses into the market on the same time schedule. Now there’s a demand for 750 homes so every Jack in town is getting in on the game, because it looks even more lucrative than before. Eventually the thing flips over because the Jacks aren’t coordinating. You end up with twenty Jacks building 2000 homes for a 750-home demand because they’re making future decisions within a mathematical system based on current demand, which is a trailing indicator of future demand.

And when you get 2000 homes in Townsville to meet a 1000 home demand, you have empty homes, busted mortgages, and whoever’s caught holding the bag loses their shirt. Then nothing gets built for three years until the overbuilt demand is scooped up, and suddenly Townsville is behind the eight ball again.

And the flag flaps in the breeze.

Not all markets are like this. Agricultural fluctuations are basically annual because they’re tied to the seasons. I imagine the market for disposable paper cups can adjust to meet demand changes quarterly. But construction is a very large very heavy pendulum, because the lag time from concept to completion is half a decade or more, and the costs involved are tremendous. Construction is around 5% of the whole economy, and when it tanks, people notice, and it always tanks because of its overcorrecting nature.

The Period

Let’s shelve Covid-19 for a second, because shelving it is important, and look at an article tracking construction spending from May of 2019.

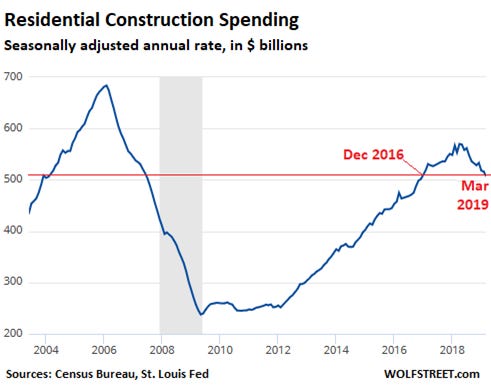

Residential construction is starting to make folks nervous. Total residential construction spending - 99% is "private" rather than "public" spending - dropped 8.4% from a year ago, the sixth month in a row of year-over-year declines, to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $507 billion, according to the Census Bureau this morning. This was down 11% from the peak in April 2018, and the lowest annual rate since December 2016.

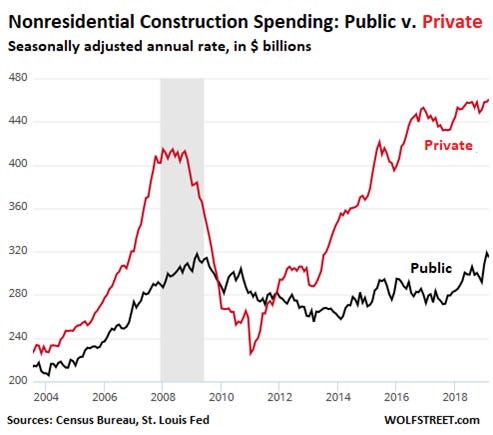

During the Great Recession, private nonresidential construction spending collapsed by over 40% in a short period of time, from an annual rate of $420 billion to $240 billion. Public construction rose until March 2009, and then as states and municipalities got squeezed by the budgetary effects of the Great Recession, with California famously running out of money and having to pay bills with IOUs for the second time in its history, projects got trimmed back or cancelled, and public construction spending began to decline.

It took 10 years, and 10 years of inflation, to bring public construction back to where it had been in March 2009. This was boosted by a surge that started at the end of 2017: in those 15 months, public construction spending jumped 11%.

That ten-year figure in the quote is important. My father used to say he could set his watch by the ten year construction cycle, because he got laid off every ten years. We had a construction crash in 2009, which was blamed on the mortgage backed securities bubble, a construction crash in 1999 which was blamed on the dot com bubble, and a construction crash in 1990 which was blamed on the S&L Crisis. But they always happen around ten years apart, plus or minus a year. We were due for one in 2020 and everyone in the industry knew it. I thought 2020 was going to be awful. Turns out it was awful for everyone but us.

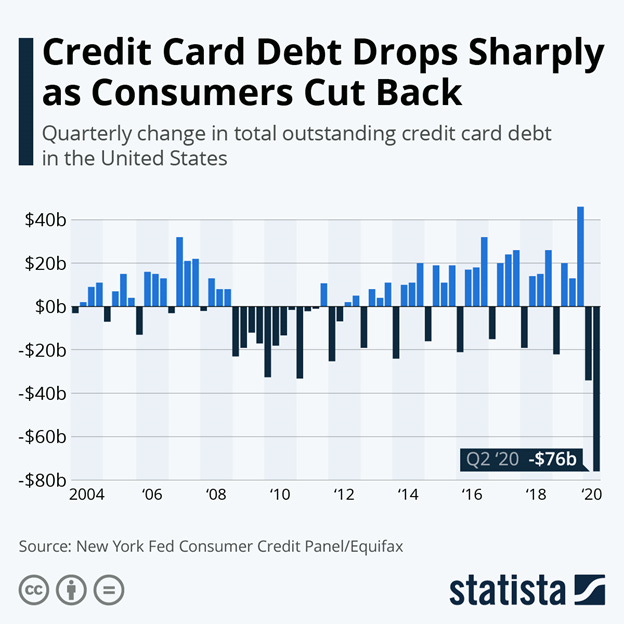

When Covid-19 hit and we had our great self-imposed recession, the government reacted by printing 25% of the entire United States money supply in one year. They handed a fair chunk of that out to the people hiding under their beds afraid of germs, who in turn used it to pay off their credit cards.

No surprise there. That’s what the banks did with the 2008 bailout – they cleared their balance sheets instead of giving out loans to people. This time around the people cleared their balance sheets, sticking the banks with cash they didn’t want because banks aren’t in the business of holding cash, they’re in the business of making interest on loans. With the threat of inflation rising, and no consumers to loan the money to on the retail side, they threw it into something “real.” Real estate. New mortgages and land development.

2020 was supposed to be the crash year, and instead it turned into the best year for land development in the history of land development, except one, 2021. I worked until midnight at least three days a week all 2021 to stay on top of the construction projects. Part of it was people fleeing cities. Part was people stuck at home renovating their houses. Part was the entire economy turning into Amazon Bait. I cannot tell you how many light industrial cross dock facilities I’ve been involved with the past two years. But all of that is gasoline on the fire, and it’s all about to crash two years later than it should have.

Signs From the Inside

As the above cycle matures, certain things start to happen, from the perspective of a civil engineer in land development. Your clients start out very professional, but over time more rookies get into the game. Over time your Accounts Receivable (“AR”) Aging starts to get longer and longer, as developers become cash stretched or their investors start to get sketchy. Over time the projects get more and more speculative and have more and more changes midstream due to the demands of different financiers. Over time the sites you’re developing are more and more constrained. Eventually half the projects you’re looking at are by rookies with high demands and no cash trying to develop land on wetlands in floodplains with environmental constraints they don’t understand, pulling loans on projects that are doomed because they don’t realize that’s a dumb idea.

All of this is transpiring now in the development market, at a peak that’s peaking two years later than the apparent peak should have been, as the stimulus money that propped the whole house of cards up is finally drying up. The supply chain issues, and the international grain shortage, and the international oil shortage, and domestic gas prices, and the war in Ukraine, and the inflationary pressures from not only the 2020 money printing press insanity but also the lockdowns, are purely additional environmental factors. This would have happened anyway, so to imagine it won’t happen now boggles my mind.

I think land development crashes no later than fourth quarter of 2022. It may happen as soon as the summer. I think it will probably be the canary in the coal mine for the overall recession that Deutsche Bank predicts for 2023. I think the predictions that the recession will be “shallow” are not rooted in an understanding of what’s happening in certain market sectors, construction among those.

I think I’m going to end up with a lot more free time later this year, and will be able to write a lot more articles. It’s going to be very unprofitable, but after the last two years I could use the break.

I can't argue with such an analysis based on history. OTOH, we are entering some very odd times created by free money. Because free money all savings had to go to stock shares and we saw impossible P/E ratios. When Tesla is 'worth' more that all auto makers combined, we clearly are nuts. The hedges know that bubble must burst and started buying whatever real property they could, tangible assets. So the price escalation in that property accelerated along with rents. We get classic inflation too much money chasing too few goods amplified by people who hadn't needed to work. That too created a pendulum that now is beginning to swing. If wage-price stuff takes hold, Katie bar the door.

Now clearly servicing the debt is touted as essential to dollar stability. As the Fed increases rates that service will eat up a lot of outlays which require actual money. Who knows what Congress will do? We may discover that we really can't print forever.

Meanwhile what are we to do with a world awash in cash? Maybe land trading among greater fools is about to take off. A lot of sunk money possible after the next crash. Building has been an important part of the economy as well as jobs. I can see a lot of angry people.

Sometimes I wish I were smarter.

There's a subdivision named Rivendell here, which was bad enough, but now we're working on King's Landing. I wish I was making that up.