We’re currently in a ramp up to the worst inflation since at least the 1970s, and while this has completely blindsided the Keynesian economists and the Modern Monetary Theory crowd, all the Austrian school economists (however many left there are) predicted this back in 2020 during the lockdowns. The problem with the Ron Paul Austrians is they’ve been predicting inflation for forever and it keeps not coming true, so people basically quit trusting them. That’s because their prior predictions weren’t looking widely enough at how the fundamental value of money is derived, and the best way to explain this is with hamburgers. Let’s talk about hamburgers in a simplified economic model. In this simple model we will lump “fiscal policy,” which is how much the government spends, and “monetary policy,” which is what the Federal Reserve Bank does to try and spin plates, into one aggregate thing. On to the hamburgers.

Hamburger Model

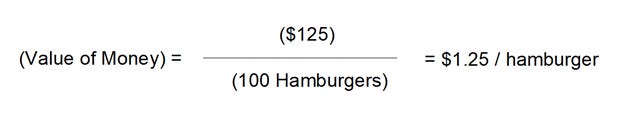

Your entire economy is made from one hundred people who do nothing but eat hamburgers. Hamburger consumers. The entire money supply in this economy is one hundred dollars. The entire national product of this economy is one hundred hamburgers per day. There is nothing to buy but hamburgers, and they each eat one hamburger per unit of time, so each hamburger is worth a dollar. This is a static system, with no inflation. The equation looks like this.

If you are educated on the subject, you know that this is a horribly simplified view of Austrian Economics as applied to the concept of floating currency, and I agree with you, but we are moving on with our article for dummies because it’s for dummies. When we do the math, it works out like this:

Each dollar is worth one hamburger. Let’s continue.

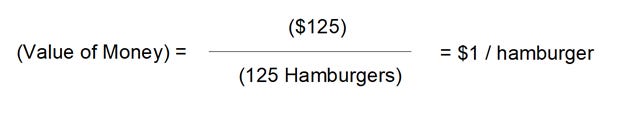

If the government were to print $25 additional dollars to add to the money supply, but the total number of hamburgers (stuff) didn’t change, then we’d see 25% inflation. Like this:

In this case, the government adding to the money supply increased the cost of buying one hamburger by 25%, up from a dollar to a dollar and twenty-five cents, because of their monetary policy. And the Ron Paul kids all freak out. But that’s not a fair way of looking at it. Let’s pretend the government added twenty-five extra dollars to the money supply, but in the same stroke increased the production of hamburgers by 25%, and also increased the demand for hamburgers by 25%. In that case, there would be no inflation. Here’s the math.

The fundamental tension between the fiscal conservatives and the fiscal liberals is, in the end, an argument about whether the additional money printed to cover the cost of the government program they’re pushing will also increase the amount of stuff, because if it increases the amount of stuff commensurately with the money printing then the money is still worth the same and we don’t see inflation.

This is fabulously difficult to measure, because while we have a pretty good idea how much money we’re printing, we have a very poor understanding of the denominator, the (stuff). It’s not just hamburgers. It’s cars and commodities, but it’s also movies and music and intellectual property and new phone apps that reduce our costs for other things and therefore have value, and it’s church and vacations and Burning Man (which is incredibly expensive to attend for being a “commerce free” venture) and the whole bucket. Buying a Gucci bag may give someone self-esteem, which has value. It just gets tortuously complicated to figure out exactly how to quantify the (stuff) in the denominator, and those torturous complications act as cover for silly alternate theories of inflation, and then economists specialize in those fake and very wrong alternate theories and win Nobel Prizes.

Let’s stick to hamburgers for now.

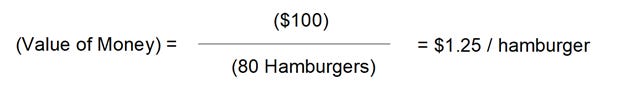

You can end up with inflation even if you don’t add to the money supply, by messing about with the denominator. If your hamburger economy has a money supply of $100 but for some reason the supply of hamburgers goes down, then the math might look like this.

Look at that. We got 25% inflation without even printing any new money at all, because the hamburger supply went down. The first lesson here is that additions to the money supply do not necessarily cause inflation, provided the money supply increase is paired with an increase in (stuff). The second lesson is that a decrease in stuff will cause inflation even if the money supply is fixed. To avoid inflation in a scenario where you decrease stuff, you’d have to reduce the money supply. And the absolute worst thing the government could ever possibly do for inflation is to increase the money supply while also intentionally decreasing the stuff.

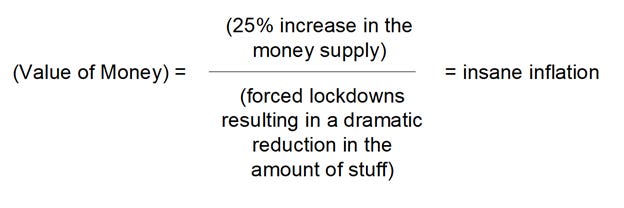

While it’s normally very difficult for government to directly affect the amount of stuff, this turns out to be exactly what we did in 2020 because of Covid fear.

In 2020 we printed a full 25% of the entire United States money supply in one go, and we handed it out to everyone, while telling everyone “non-essential” to stop making stuff. The few remaining qualified Austrian economists screamed bloody murder at how horribly dangerous to the economy this was, but because the Ron Paul kids had been crying wolf about inflation for decades because they only looked at the numerator, nobody listened to the qualified Austrian economists also looking at the denominator.

“But the 2008 bailouts didn’t cause inflation” you say. Here’s the thing. The 2008 bailouts went straight to the banks, not to the people who technically needed the money. That was arguably worse from an ethical standpoint than the 2020 bailout, but it wasn’t inflationary because the money went into the hands of very few people. It was as if someone in Hamburger Land increased the money supply 25% but gave all that money to one dude, and that one dude still only bought one hamburger with it. That one dude is enriched unfairly but there’s no inflation because the money added isn’t “moving around.” This then leads into the discussion of the “velocity of money,” which is important but too complicated to cover here in our Dummies model.

When viewed through the simple Austrian lens, it’s clear that the only way to avoid extreme inflation would have been to (A) don’t bail out but also (B) don’t shut down. If you’re going to bail out, then you have to actually increase the amount of stuff, not decrease it, to keep inflation in check. This analysis lens also leads us to some ugly conclusions. For one, inflation is impossible to avoid at this point, and two, the only way to curb it is to burn money or make more stuff to buy or both. “Build Back Better” must necessarily include “work harder to manufacture more stuff,” and printing more money during “Build Back Better” means you must manufacture even more stuff.

So yes, this is Biden's fault, but also Trump's, and every Democrat's, and every Republican's, and it's on the CDC, and the FDA, and the corresponding international entities corresponding to these domestic ones across the entire global connected economy. It is on China in particular, for shutting manufacturing down, and also on us for relying on China for our manufacturing. It’s also on the choices individual people made during 2020 to reduce their consumption while they collected these bailout checks, because the individuals were scared of germs. Basically everyone is at fault here.

Pucker up.

I have long been fascinated at the wealth created out of nothing tangible aside from the labor involved in the creation of some IP. Three guys writing software for a year collecting $3B. The value in the equation stems apparently via ad dollars in a somewhat zero sum game. The old paradigm of wealth resulting from exploiting natural resources via labor and IP got removed in the new economy, One day another exposition along this fine hamburger story would be helpful.

Thanks as always,

So can the metaverse save us?