Twelve days ago I appeared on the Rebel Wisdom podcast discussing the topic of “egregores” as a modern social internet phenomena, and the application of that analysis to Covid sensemaking. The echoes of this appearance still reverberate on Twitter, tied largely up with smart people arguing about whether egregores have agency, whether they have any kind of consciousness, and whether they could have one without the other.

This article isn’t about that.

This article is about one of the curious bounce backs from the podcast, as the internet grabbed it, churned it, and made new things out of it. This article is about the music of the new. The synthesis of knowledge by referential means. The ways in which neural connections are made in the global netbrain.

In a former life I was a DJ at WREK Atlanta, and founded The Mobius, which remains to this day the longest running electronic music specialty show in the southeastern United States. At the time, in the 1990s, electronic music was still in an emergent growth phase, and the people involved in its production spent a lot of time talking about high concepts that have since leaked out into all aspects of our modern internet zeitgeist. One of them was Aural Hypertext.

Aural Hypertext

I don’t recall exactly where I first heard this term, but I believe it was in an NPR interview with DJ Spooky That Subliminal Kid.

The interview fades from my mind, and is not readily Googlable given the time and place it happened, so perhaps I’m imagining all of it or misconstruing it through the fog of memory detached from the shared memory bank that is the web. But I recall the gist of it being something like this. When an electronic musician samples an older song to mix that sample into a new work, they create a mental link back to that prior work, and all of the memory and embodiment of that prior work becomes embedded in the new song. Then when another musician samples that song, the memory of both works becomes embodied in the new work. And so forth until, at the pinnacle of the Great Tree of Remixes, you have the Uber Song, a collective work which is entirely referential and yet entirely a synthesis of all prior works.

This was the kind of crap we used to talk about, back then.

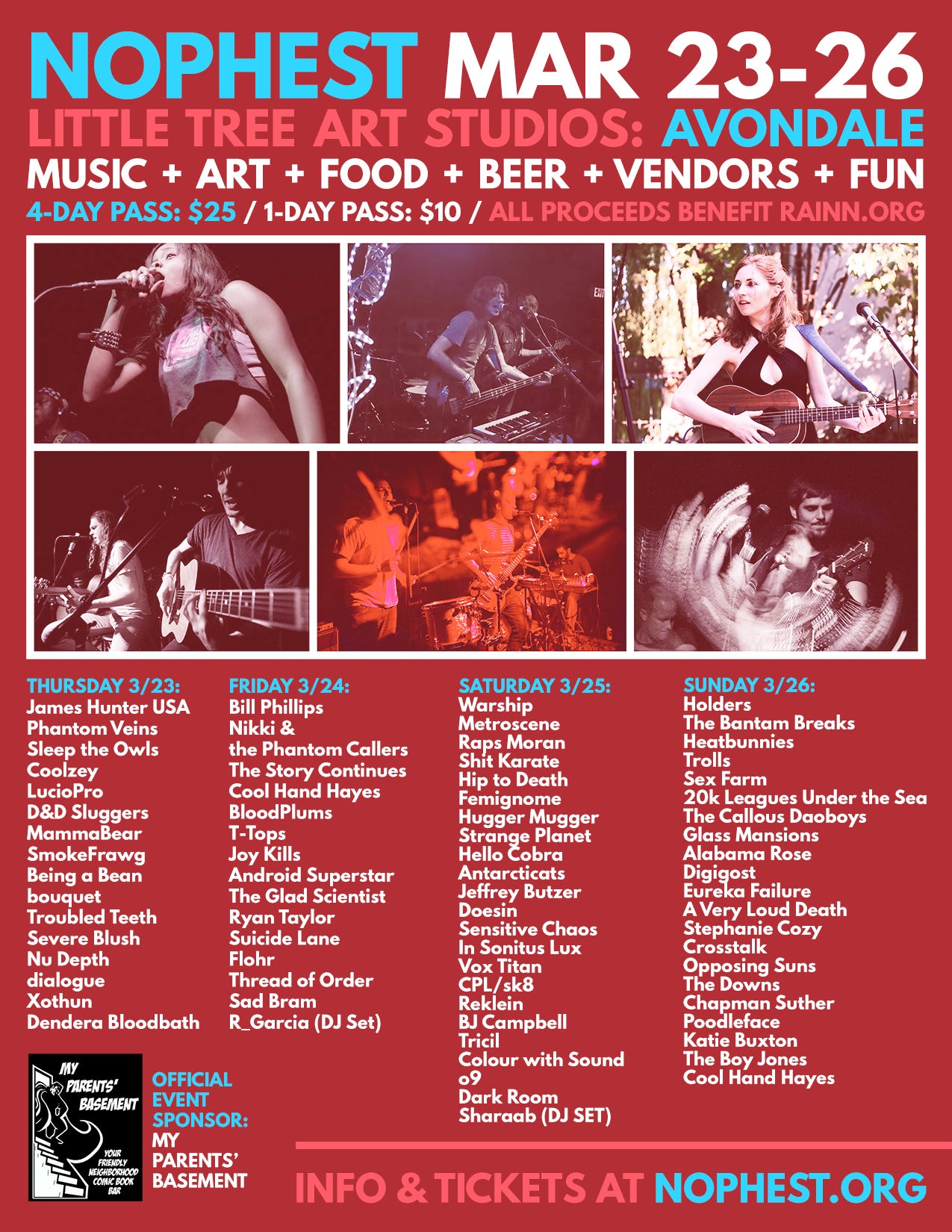

Electronic music has now fully matured and captured almost all elements of all other genres. Very few musicians of any genre perform without someone in the back running a sample bank in Ableton Live. Some musicians, such as myself, perform entirely out of this sample bank, with clips and instrumentation performed previously, and focus all our performance on creating a unique-to-the-moment live mix of prior instrumentation. Like this benefit show I did for RAINN:

Some musicians don’t even bother to do this. A controversial tumblr post a decade ago by Deadmau5 exposed the most prominent EDM acts of the time when he said, “we all just hit play,” meaning the complicated Ableton project in the background was not merely the only thing running, but it was running itself and the famous EDM acts behind the decks were basically dancing around and faking the whole thing. Millie Vanilli for the modern age. Maui Threv, a fellow of mine at WREK who took up the Mobius mantle after I retired, once famously did an entire “two laptop set” by pressing play on one laptop and installing Windows on the other laptop, on stage.

The Medium is The Message

Marshall McLuhan stated in his 1964 opus on emergent media of the day, “The Medium Is The Message.” We at the radio show used to apply his theories to our arguments about electronic music. At the time in the 90s, there was a great schism among club DJs about whether or not to pivot from spinning vinyl to CDs, and to understand the schism, which I assure you was very deep, we have to talk a bit about the evolution of electronic music.

Modern electronic music traces one of its roots to travelling Jamaican “sound systems” which would set up and throw parties for villages. They would blend live instrumentation with delay effects boxes and tape loops, overdubbing a recording onto a mobius loop of magnetic tape while playing it at the same time, to create unique repetitions that formed the backbone for “Dub Music.” Lee Scratch Perry was a notable artist, and heavily influential on more modern electronic acts such as The Orb.

Hip hop began using turntables as an instrument themselves in the late 1970s and early 1980s. House music emerged in the late 1980s in Chicago and other US urban centers, and built itself around a concept known as the “continuous beat matched set,” where a DJ would play music for a party from a host of records which all had approximately the same tempo and beat signature, and the DJ would mix the audio from two records together on the fly by adjusting the pitch settings so the tempos matched, beats matched, crossfading between the two records so the music never stopped. They took twelve songs and made one giant song from them and the dancing continued.

Circle to the 1990s. The first step to becoming a talented club DJ in the 90s was learning to beat match vinyl. The second step was buying a whole ass ton of vinyl, and the third was figuring out what to do creatively with the first two steps. This took practice and skill and investment. The emergence of CDJ rigs, which played compact disks instead of vinyl, automated these steps, removing the need for beatmatching skills and lowering the bar for vinyl collection. And there was a great wailing and gnashing of teeth at the time among the vinyl DJs that using these tools was not being a “real musician.”

But the punk bands looked at the vinyl DJs and said they weren’t real musicians. And the jazz ensembles looked at the punk bands and said they weren’t real musicians. And the dude playing third violin in the Atlanta symphony making crap wages with his Juilliard diploma looked at the whole mess and groaned while he ate ramen.

We went meta. If Mr. Julliard was a musician, and so was the punk band, and so was the vinyl DJ, then obviously the CDJ DJ was a musician, and as the tools scaled every link in the chain was a musician. We at The Mobius were doing radio sets by blending vinyl, CDs, stuff from these new Apple portable hard drives (“iPods”), old 8 track carts, 1970s reel to reel recordings from Vietnam, and even playing transistor radio signals from police scanners into the station microphone, mixing it all up. Our instrument wasn’t even the CDJ, our instrument extended all the way to the 40-kilowatt antenna near 10th Street, and by extension, the speakers in people’s cars. And now the internet is itself the tool. Youtube is an instrument. The medium is the message.

Rebel Wisdom and The Meta Egregore

This thing from the 1990s continues with new technology, and it happened to me, without my permission or knowledge, but the results of it are really weird and worth sharing. This is the Rebel Wisdom podcast with David Fuller:

This is the first-tier abstraction of the podcast, a blend of commentary and reaction video by Paul VanderKlay, a Christian minister, Jordan Peterson fan, and IDW critic who uses elements of this corner of internet thought in his theological arguments:

I’ve skimmed most of it, and I would characterize it as generally in the form of “dunking on materialist atheists for discovering theological concepts without realizing it.” This dunk may or may not be applicable to David, but I got a chuckle out of it because Paul isn’t plugged in (yet) to the religious analysis layer of HWFO.

This is the second-tier abstraction:

It was put together by Chris Petkau, a member of the internet community Paul fosters who does these sorts of musical video remixes of Paul’s material for fun on his small Youtube channel. I loved it.

And in this chain of Youtubes, we can see DJ Spooky’s Aural Hypertext manifest in full. A reference of a reference of a source, the source of which is also deeply referential. These are the threads the internet is building to bind all knowledge in the memory of man.

Can't wait for Paul Vanderklay's four hour video on this post!